Matrix multiply

ARM assembler in Raspberry Pi – Chapter 14

In chapter 13 we saw the basic elements of VFPv2, the floating point subarchitecture of ARMv6. In this chapter we will implement a floating point matrix multiply using VFPv2.

Disclaimer: I advise you against using the code in this chapter in commercial-grade projects unless you fully review it for both correctness and precision.

Matrix multiply

Given two vectors v and w of rank r where v = <v0, v1, … vr-1> and w = <w0, w1, …, wr-1>, we define the dot product of v by w as the scalar v · w = v0×w0 + v1×w0 + … + vr-1×wr-1.

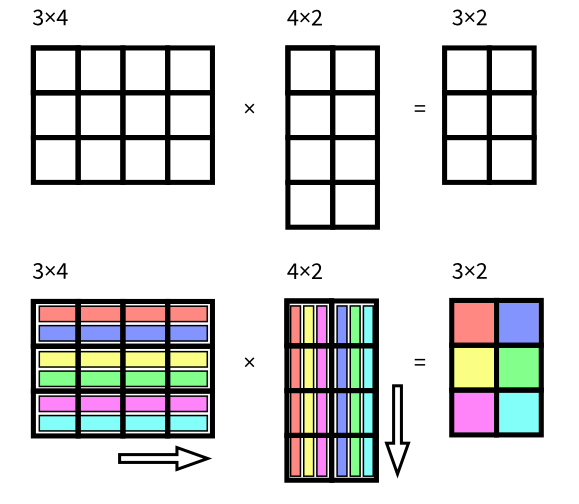

We can multiply a matrix A of n rows and m columns (n x m) by a matrix B of m rows and p columns (m x p). The result is a matrix of n rows and p columns. Matrix multiplication may seem complicated but actually it is not. Every element in the result matrix it is just the dot product (defined in the paragraph above) of the corresponding row of the matrix A by the corresponding column of the matrix B (this is why there must be as many columns in A as there are rows in B).

A straightforward implementation of the matrix multiplication in C is as follows.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | float A[N][M]; // N rows of M columns each row float B[M][P]; // M rows of P columns each row // Result float C[N][P]; for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) // for each row of the result { for (int j = 0; j < P; j++) // and for each column { C[i][j] = 0; // Initialize to zero // Now make the dot matrix of the row by the column for (int k = 0; k < M; k++) C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j]; } } |

In order to simplify the example, we will asume that both matrices A and B are square matrices of size n x n. This simplifies just a bit the algorithm.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | float A[N][N]; float B[N][N]; // Result float C[N][N]; for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) { for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) { C[i][j] = 0; for (int k = 0; k < N; k++) C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j]; } } |

Matrix multiplication is an important operation used in many areas. For instance, in computer graphics is usually performed on 3×3 and 4×4 matrices representing 3D geometry. So we will try to make a reasonably fast version of it (we do not aim at making the best one, though).

A first improvement we want to do in this algorithm is making the loops perfectly nested. There are some technical reasons beyond the scope of this code for that. So we will get rid of the initialization of C[i][j] to 0, outside of the loop.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | float A[N][N]; float B[M][N]; // Result float C[N][N]; for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) C[i][j] = 0; for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) for (int k = 0; k < N; k++) C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j]; |

After this change, the interesting part of our algorithm, line 13, is inside a perfect nest of loops of depth 3.

Accessing a matrix

It is relatively straightforward to access an array of just one dimension, like in a[i]. Just get i, multiply it by the size in bytes of each element of the array and then add the address of a (the base address of the array). So, the address of a[i] is just a + ELEMENTSIZE*i.

Things get a bit more complicated when our array has more than one dimension, like a matrix or a cube. Given an access like a[i][j][k] we have to compute which element is denoted by [i][j][k]. This depends on whether the language is row-major order or column-major order. We assume row-major order here (like in C language). So [i][j][k] must denote k + j * NK + i * NK * NJ, where NK and NJ are the number of elements in every dimension. For instance, a three dimensional array of 3 x 4 x 5 elements, the element [1][2][3] is 3 + 2 * 5 + 1 * 5 * 4 = 23 (here NK = 5 and NJ = 4. Note that NI = 3 but we do not need it at all). We assume that our language indexes arrays starting from 0 (like C). If the language allows a lower bound other than 0, we first have to subtract the lower bound to get the position.

We can compute the position in a slightly better way if we reorder it. Instead of calculating k + j * NK + i * NK * NJ we will do k + NK * (j + NJ * i). This way all the calculus is just a repeated set of steps calculating x + Ni * y like in the example below.

/* Calculating the address of C[i][j][k] declared as int C[3][4][5] */ /* &C[i][j][k] is, thus, C + ELEMENTSIZE * ( k + NK * (j + NJ * i) ) */ // Assume i is in r4, j in r5 and k in r6 and the base address of C in r3 */ mov r8, #4 /* r8 ← NJ (Recall that NJ = 4) */ mul r7, r8, r4 /* r7 ← NJ * i */ add r7, r5, r7 /* r7 ← j + NJ * i */ mov r8, #5 /* r8 ← NK (Recall that NK = 5) */ mul r7, r8, r7 /* r7 ← NK * (j + NJ * i) */ add r7, r6, r7 /* r7 ← k + NK * (j + NJ + i) */ mov r8, #4 /* r8 ← ELEMENTSIZE (Recall that size of an int is 4 bytes) */ mul r7, r8, r7 /* r7 ← ELEMENTSIZE * ( k + NK * (j + NJ * i) ) */ add r7, r3, r7 /* r7 ← C + ELEMENTSIZE * ( k + NK * (j + NJ * i) ) */ |

Naive matrix multiply of 4×4 single-precision

As a first step, let’s implement a naive matrix multiply that follows the C algorithm above according to the letter.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 | /* -- matmul.s */ .data mat_A: .float 0.1, 0.2, 0.0, 0.1 .float 0.2, 0.1, 0.3, 0.0 .float 0.0, 0.3, 0.1, 0.5 .float 0.0, 0.6, 0.4, 0.1 mat_B: .float 4.92, 2.54, -0.63, -1.75 .float 3.02, -1.51, -0.87, 1.35 .float -4.29, 2.14, 0.71, 0.71 .float -0.95, 0.48, 2.38, -0.95 mat_C: .float 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0 .float 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0 .float 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0 .float 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0 .float 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0 format_result : .asciz "Matrix result is:\n%5.2f %5.2f %5.2f %5.2f\n%5.2f %5.2f %5.2f %5.2f\n%5.2f %5.2f %5.2f %5.2f\n%5.2f %5.2f %5.2f %5.2f\n" .text naive_matmul_4x4: /* r0 address of A r1 address of B r2 address of C */ push {r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, lr} /* Keep integer registers */ /* First zero 16 single floating point */ /* In IEEE 754, all bits cleared means 0 */ mov r4, r2 mov r5, #16 mov r6, #0 b .Lloop_init_test .Lloop_init : str r6, [r4], +#4 /* *r4 ← r6 then r4 ← r4 + 4 */ .Lloop_init_test: subs r5, r5, #1 bge .Lloop_init /* We will use r4 as i r5 as j r6 as k */ mov r4, #0 /* r4 ← 0 */ .Lloop_i: /* loop header of i */ cmp r4, #4 /* if r4 == 4 goto end of the loop i */ beq .Lend_loop_i mov r5, #0 /* r5 ← 0 */ .Lloop_j: /* loop header of j */ cmp r5, #4 /* if r5 == 4 goto end of the loop j */ beq .Lend_loop_j /* Compute the address of C[i][j] and load it into s0 */ /* Address of C[i][j] is C + 4*(4 * i + j) */ mov r7, r5 /* r7 ← r5. This is r7 ← j */ adds r7, r7, r4, LSL #2 /* r7 ← r7 + (r4 << 2). This is r7 ← j + i * 4. We multiply i by the row size (4 elements) */ adds r7, r2, r7, LSL #2 /* r7 ← r2 + (r7 << 2). This is r7 ← C + 4*(j + i * 4) We multiply (j + i * 4) by the size of the element. A single-precision floating point takes 4 bytes. */ vldr s0, [r7] /* s0 ← *r7 */ mov r6, #0 /* r6 ← 0 */ .Lloop_k : /* loop header of k */ cmp r6, #4 /* if r6 == 4 goto end of the loop k */ beq .Lend_loop_k /* Compute the address of a[i][k] and load it into s1 */ /* Address of a[i][k] is a + 4*(4 * i + k) */ mov r8, r6 /* r8 ← r6. This is r8 ← k */ adds r8, r8, r4, LSL #2 /* r8 ← r8 + (r4 << 2). This is r8 ← k + i * 4 */ adds r8, r0, r8, LSL #2 /* r8 ← r0 + (r8 << 2). This is r8 ← a + 4*(k + i * 4) */ vldr s1, [r8] /* s1 ← *r8 */ /* Compute the address of b[k][j] and load it into s2 */ /* Address of b[k][j] is b + 4*(4 * k + j) */ mov r8, r5 /* r8 ← r5. This is r8 ← j */ adds r8, r8, r6, LSL #2 /* r8 ← r8 + (r6 << 2). This is r8 ← j + k * 4 */ adds r8, r1, r8, LSL #2 /* r8 ← r1 + (r8 << 2). This is r8 ← b + 4*(j + k * 4) */ vldr s2, [r8] /* s1 ← *r8 */ vmul.f32 s3, s1, s2 /* s3 ← s1 * s2 */ vadd.f32 s0, s0, s3 /* s0 ← s0 + s3 */ add r6, r6, #1 /* r6 ← r6 + 1 */ b .Lloop_k /* next iteration of loop k */ .Lend_loop_k: /* Here ends loop k */ vstr s0, [r7] /* Store s0 back to C[i][j] */ add r5, r5, #1 /* r5 ← r5 + 1 */ b .Lloop_j /* next iteration of loop j */ .Lend_loop_j: /* Here ends loop j */ add r4, r4, #1 /* r4 ← r4 + 1 */ b .Lloop_i /* next iteration of loop i */ .Lend_loop_i: /* Here ends loop i */ pop {r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, lr} /* Restore integer registers */ bx lr /* Leave function */ .globl main main: push {r4, r5, r6, lr} /* Keep integer registers */ vpush {d0-d1} /* Keep floating point registers */ /* Prepare call to naive_matmul_4x4 */ ldr r0, addr_mat_A /* r0 ← a */ ldr r1, addr_mat_B /* r1 ← b */ ldr r2, addr_mat_C /* r2 ← c */ bl naive_matmul_4x4 /* Now print the result matrix */ ldr r4, addr_mat_C /* r4 ← c */ vldr s0, [r4] /* s0 ← *r4. This is s0 ← c[0][0] */ vcvt.f64.f32 d1, s0 /* Convert it into a double-precision d1 ← s0 */ vmov r2, r3, d1 /* {r2,r3} ← d1 */ mov r6, sp /* Remember the stack pointer, we need it to restore it back later */ /* r6 ← sp */ mov r5, #1 /* We will iterate from 1 to 15 (because the 0th item has already been handled */ add r4, r4, #60 /* Go to the last item of the matrix c, this is c[3][3] */ .Lloop: vldr s0, [r4] /* s0 ← *r4. Load the current item */ vcvt.f64.f32 d1, s0 /* Convert it into a double-precision d1 ← s0 */ sub sp, sp, #8 /* Make room in the stack for the double-precision */ vstr d1, [sp] /* Store the double precision in the top of the stack */ sub r4, r4, #4 /* Move to the previous element in the matrix */ add r5, r5, #1 /* One more item has been handled */ cmp r5, #16 /* if r5 != 16 go to next iteration of the loop */ bne .Lloop ldr r0, addr_format_result /* r0 ← &format_result */ bl printf /* call printf */ mov sp, r6 /* Restore the stack after the call */ mov r0, #0 vpop {d0-d1} pop {r4, r5, r6, lr} bx lr addr_mat_A : .word mat_A addr_mat_B : .word mat_B addr_mat_C : .word mat_C addr_format_result : .word format_result |

That’s a lot of code but it is not complicated. Unfortunately computing the address of the array takes an important number of instructions. In our naive_matmul_4x4 we have the three loops i, j and k of the C algorithm. We compute the address of C[i][j] in the loop j (there is no need to compute it every time in the loop k) in lines 52 to 63. The value contained in C[i][j] is then loaded into s0. In each iteration of loop k we load A[i][k] and B[k][j] in s1 and s2 respectively (lines 70 to 82). After the loop k ends, we can store s0 back to the array position (kept in r7, line 90)

In order to print the result matrix we have to pass 16 floating points to printf. Unfortunately, as stated in chapter 13, we have to first convert them into double-precision before passing them. Note also that the first single-precision can be passed using registers r2 and r3. All the remaining must be passed on the stack and do not forget that the stack parameters must be passed in opposite order. This is why once the first element of the C matrix has been loaded in {r2,r3} (lines 117 to 120) we advance 60 bytes r4. This is C[3][3], the last element of the matrix C. We load the single-precision, convert it into double-precision, push it in the stack and then move backwards register r4, to the previous element in the matrix (lines 128 to 137). Observe that we use r6 as a marker of the stack, since we need to restore the stack once printf returns (line 122 and line 141). Of course we could avoid using r6 and instead do add sp, sp, #120 since this is exactly the amount of bytes we push to the stack (15 values of double-precision, each taking 8 bytes).

I have not chosen the values of the two matrices randomly. The second one is (approximately) the inverse of the first. This way we will get the identity matrix (a matrix with all zeros but a diagonal of ones). Due to rounding issues the result matrix will not be the identity, but it will be pretty close. Let’s run the program.

$ ./matmul Matrix result is: 1.00 -0.00 0.00 0.00 -0.00 1.00 0.00 -0.00 0.00 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 -0.00 0.00 1.00

Vectorial approach

The algorithm we are trying to implement is fine but it is not the most optimizable. The problem lies in the way the loop k accesses the elements. Access A[i][k] is eligible for a multiple load as A[i][k] and A[i][k+1] are contiguous elements in memory. This way we could entirely avoid all the loop k and perform a 4 element load from A[i][0] to A[i][3]. The access B[k][j] does not allow that since elements B[k][j] and B[k+1][j] have a full row inbetween. This is a strided access (the stride here is a full row of 4 elements, this is 16 bytes), VFPv2 does not allow a strided multiple load, so we will have to load one by one.. Once we have all the elements of the loop k loaded, we can do a vector multiplication and a sum.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 | naive_vectorial_matmul_4x4: /* r0 address of A r1 address of B r2 address of C */ push {r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, lr} /* Keep integer registers */ vpush {s16-s19} /* Floating point registers starting from s16 must be preserved */ vpush {s24-s27} /* First zero 16 single floating point */ /* In IEEE 754, all bits cleared means 0 */ mov r4, r2 mov r5, #16 mov r6, #0 b .L1_loop_init_test .L1_loop_init : str r6, [r4], +#4 /* *r4 ← r6 then r4 ← r4 + 4 */ .L1_loop_init_test: subs r5, r5, #1 bge .L1_loop_init /* Set the LEN field of FPSCR to be 4 (value 3) */ mov r5, #0b011 /* r5 ← 3 */ mov r5, r5, LSL #16 /* r5 ← r5 << 16 */ fmrx r4, fpscr /* r4 ← fpscr */ orr r4, r4, r5 /* r4 ← r4 | r5 */ fmxr fpscr, r4 /* fpscr ← r4 */ /* We will use r4 as i r5 as j r6 as k */ mov r4, #0 /* r4 ← 0 */ .L1_loop_i: /* loop header of i */ cmp r4, #4 /* if r4 == 4 goto end of the loop i */ beq .L1_end_loop_i mov r5, #0 /* r5 ← 0 */ .L1_loop_j: /* loop header of j */ cmp r5, #4 /* if r5 == 4 goto end of the loop j */ beq .L1_end_loop_j /* Compute the address of C[i][j] and load it into s0 */ /* Address of C[i][j] is C + 4*(4 * i + j) */ mov r7, r5 /* r7 ← r5. This is r7 ← j */ adds r7, r7, r4, LSL #2 /* r7 ← r7 + (r4 << 2). This is r7 ← j + i * 4. We multiply i by the row size (4 elements) */ adds r7, r2, r7, LSL #2 /* r7 ← r2 + (r7 << 2). This is r7 ← C + 4*(j + i * 4) We multiply (j + i * 4) by the size of the element. A single-precision floating point takes 4 bytes. */ /* Compute the address of a[i][0] */ mov r8, r4, LSL #2 adds r8, r0, r8, LSL #2 vldmia r8, {s8-s11} /* Load {s8,s9,s10,s11} ← {a[i][0], a[i][1], a[i][2], a[i][3]} */ /* Compute the address of b[0][j] */ mov r8, r5 /* r8 ← r5. This is r8 ← j */ adds r8, r1, r8, LSL #2 /* r8 ← r1 + (r8 << 2). This is r8 ← b + 4*(j) */ vldr s16, [r8] /* s16 ← *r8. This is s16 ← b[0][j] */ vldr s17, [r8, #16] /* s17 ← *(r8 + 16). This is s17 ← b[1][j] */ vldr s18, [r8, #32] /* s18 ← *(r8 + 32). This is s17 ← b[2][j] */ vldr s19, [r8, #48] /* s19 ← *(r8 + 48). This is s17 ← b[3][j] */ vmul.f32 s24, s8, s16 /* {s24,s25,s26,s27} ← {s8,s9,s10,s11} * {s16,s17,s18,s19} */ vmov.f32 s0, s24 /* s0 ← s24 */ vadd.f32 s0, s0, s25 /* s0 ← s0 + s25 */ vadd.f32 s0, s0, s26 /* s0 ← s0 + s26 */ vadd.f32 s0, s0, s27 /* s0 ← s0 + s27 */ vstr s0, [r7] /* Store s0 back to C[i][j] */ add r5, r5, #1 /* r5 ← r5 + 1 */ b .L1_loop_j /* next iteration of loop j */ .L1_end_loop_j: /* Here ends loop j */ add r4, r4, #1 /* r4 ← r4 + 1 */ b .L1_loop_i /* next iteration of loop i */ .L1_end_loop_i: /* Here ends loop i */ /* Set the LEN field of FPSCR back to 1 (value 0) */ mov r5, #0b011 /* r5 ← 3 */ mvn r5, r5, LSL #16 /* r5 ← ~(r5 << 16) */ fmrx r4, fpscr /* r4 ← fpscr */ and r4, r4, r5 /* r4 ← r4 & r5 */ fmxr fpscr, r4 /* fpscr ← r4 */ vpop {s24-s27} /* Restore preserved floating registers */ vpop {s16-s19} pop {r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, lr} /* Restore integer registers */ bx lr /* Leave function */ |

With this approach we can entirely remove the loop k, as we do 4 operations at once. Note that we have to modify fpscr so the field len is set to 4 (and restore it back to 1 when leaving the function).

Fill the registers

In the previous version we are not exploiting all the registers of VFPv2. Each rows takes 4 registers and so does each column, so we end using only 8 registers plus 4 for the result and one in the bank 0 for the summation. We got rid the loop k to process C[i][j] at once. What if we processed C[i][j] and C[i][j+1] at the same time? This way we can fill all the 8 registers in each bank.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 | naive_vectorial_matmul_2_4x4: /* r0 address of A r1 address of B r2 address of C */ push {r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, lr} /* Keep integer registers */ vpush {s16-s31} /* Floating point registers starting from s16 must be preserved */ /* First zero 16 single floating point */ /* In IEEE 754, all bits cleared means 0 */ mov r4, r2 mov r5, #16 mov r6, #0 b .L2_loop_init_test .L2_loop_init : str r6, [r4], +#4 /* *r4 ← r6 then r4 ← r4 + 4 */ .L2_loop_init_test: subs r5, r5, #1 bge .L2_loop_init /* Set the LEN field of FPSCR to be 4 (value 3) */ mov r5, #0b011 /* r5 ← 3 */ mov r5, r5, LSL #16 /* r5 ← r5 << 16 */ fmrx r4, fpscr /* r4 ← fpscr */ orr r4, r4, r5 /* r4 ← r4 | r5 */ fmxr fpscr, r4 /* fpscr ← r4 */ /* We will use r4 as i r5 as j */ mov r4, #0 /* r4 ← 0 */ .L2_loop_i: /* loop header of i */ cmp r4, #4 /* if r4 == 4 goto end of the loop i */ beq .L2_end_loop_i mov r5, #0 /* r5 ← 0 */ .L2_loop_j: /* loop header of j */ cmp r5, #4 /* if r5 == 4 goto end of the loop j */ beq .L2_end_loop_j /* Compute the address of C[i][j] and load it into s0 */ /* Address of C[i][j] is C + 4*(4 * i + j) */ mov r7, r5 /* r7 ← r5. This is r7 ← j */ adds r7, r7, r4, LSL #2 /* r7 ← r7 + (r4 << 2). This is r7 ← j + i * 4. We multiply i by the row size (4 elements) */ adds r7, r2, r7, LSL #2 /* r7 ← r2 + (r7 << 2). This is r7 ← C + 4*(j + i * 4) We multiply (j + i * 4) by the size of the element. A single-precision floating point takes 4 bytes. */ /* Compute the address of a[i][0] */ mov r8, r4, LSL #2 adds r8, r0, r8, LSL #2 vldmia r8, {s8-s11} /* Load {s8,s9,s10,s11} ← {a[i][0], a[i][1], a[i][2], a[i][3]} */ /* Compute the address of b[0][j] */ mov r8, r5 /* r8 ← r5. This is r8 ← j */ adds r8, r1, r8, LSL #2 /* r8 ← r1 + (r8 << 2). This is r8 ← b + 4*(j) */ vldr s16, [r8] /* s16 ← *r8. This is s16 ← b[0][j] */ vldr s17, [r8, #16] /* s17 ← *(r8 + 16). This is s17 ← b[1][j] */ vldr s18, [r8, #32] /* s18 ← *(r8 + 32). This is s17 ← b[2][j] */ vldr s19, [r8, #48] /* s19 ← *(r8 + 48). This is s17 ← b[3][j] */ /* Compute the address of b[0][j+1] */ add r8, r5, #1 /* r8 ← r5 + 1. This is r8 ← j + 1*/ adds r8, r1, r8, LSL #2 /* r8 ← r1 + (r8 << 2). This is r8 ← b + 4*(j + 1) */ vldr s20, [r8] /* s20 ← *r8. This is s20 ← b[0][j + 1] */ vldr s21, [r8, #16] /* s21 ← *(r8 + 16). This is s21 ← b[1][j + 1] */ vldr s22, [r8, #32] /* s22 ← *(r8 + 32). This is s22 ← b[2][j + 1] */ vldr s23, [r8, #48] /* s23 ← *(r8 + 48). This is s23 ← b[3][j + 1] */ vmul.f32 s24, s8, s16 /* {s24,s25,s26,s27} ← {s8,s9,s10,s11} * {s16,s17,s18,s19} */ vmov.f32 s0, s24 /* s0 ← s24 */ vadd.f32 s0, s0, s25 /* s0 ← s0 + s25 */ vadd.f32 s0, s0, s26 /* s0 ← s0 + s26 */ vadd.f32 s0, s0, s27 /* s0 ← s0 + s27 */ vmul.f32 s28, s8, s20 /* {s28,s29,s30,s31} ← {s8,s9,s10,s11} * {s20,s21,s22,s23} */ vmov.f32 s1, s28 /* s1 ← s28 */ vadd.f32 s1, s1, s29 /* s1 ← s1 + s29 */ vadd.f32 s1, s1, s30 /* s1 ← s1 + s30 */ vadd.f32 s1, s1, s31 /* s1 ← s1 + s31 */ vstmia r7, {s0-s1} /* {C[i][j], C[i][j+1]} ← {s0, s1} */ add r5, r5, #2 /* r5 ← r5 + 2 */ b .L2_loop_j /* next iteration of loop j */ .L2_end_loop_j: /* Here ends loop j */ add r4, r4, #1 /* r4 ← r4 + 1 */ b .L2_loop_i /* next iteration of loop i */ .L2_end_loop_i: /* Here ends loop i */ /* Set the LEN field of FPSCR back to 1 (value 0) */ mov r5, #0b011 /* r5 ← 3 */ mvn r5, r5, LSL #16 /* r5 ← ~(r5 << 16) */ fmrx r4, fpscr /* r4 ← fpscr */ and r4, r4, r5 /* r4 ← r4 & r5 */ fmxr fpscr, r4 /* fpscr ← r4 */ vpop {s16-s31} /* Restore preserved floating registers */ pop {r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, lr} /* Restore integer registers */ bx lr /* Leave function */ |

Note that because we now process j and j + 1, r5 (j) is now increased by 2 at the end of the loop. This is usually known as loop unrolling and it is always legal to do. We do more than one iteration of the original loop in the unrolled loop. The amount of iterations of the original loop we do in the unrolled loop is the unroll factor. In this case since the number of iterations (4) perfectly divides the unrolling factor (2) we do not need an extra loop for the remainder iterations (the remainder loop has one less iteration than the value of the unrolling factor).

As you can see, the accesses to b[k][j] and b[k][j+1] are starting to become tedious. Maybe we should change a bit more the matrix multiply algorithm.

Reorder the accesses

Is there a way we can mitigate the strided accesses to the matrix B? Yes, there is one, we only have to permute the loop nest i, j, k into the loop nest k, i, j. Now you may be wondering if this is legal. Well, checking for the legality of these things is beyond the scope of this post so you will have to trust me here. Such permutation is fine. What does this mean? Well, it means that our algorithm will now look like this.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | float A[N][N]; float B[M][N]; // Result float C[N][N]; for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) C[i][j] = 0; for (int k = 0; k < N; k++) for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) for (int j = 0; j < N; j++) C[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j]; |

This may seem not very useful, but note that, since now k is in the outermost loop, now it is easier to use vectorial instructions.

for (int k = 0; k < N; k++) for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) { C[i][0] += A[i][k] * B[k][0]; C[i][1] += A[i][k] * B[k][1]; C[i][2] += A[i][k] * B[k][2]; C[i][3] += A[i][k] * B[k][3]; } |

If you remember the chapter 13, VFPv2 instructions have a mixed mode when the Rsource2 register is in bank 0. This case makes a perfect match: we can load C[i][0..3] and B[k][0..3] with a load multiple and then load A[i][k] in a register of the bank 0. Then we can make multiply A[i][k]*B[k][0..3] and add the result to C[i][0..3]. As a bonus, the number of instructions is much lower.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 | better_vectorial_matmul_4x4: /* r0 address of A r1 address of B r2 address of C */ push {r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, lr} /* Keep integer registers */ vpush {s16-s19} /* Floating point registers starting from s16 must be preserved */ vpush {s24-s27} /* First zero 16 single floating point */ /* In IEEE 754, all bits cleared means 0 */ mov r4, r2 mov r5, #16 mov r6, #0 b .L3_loop_init_test .L3_loop_init : str r6, [r4], +#4 /* *r4 ← r6 then r4 ← r4 + 4 */ .L3_loop_init_test: subs r5, r5, #1 bge .L3_loop_init /* Set the LEN field of FPSCR to be 4 (value 3) */ mov r5, #0b011 /* r5 ← 3 */ mov r5, r5, LSL #16 /* r5 ← r5 << 16 */ fmrx r4, fpscr /* r4 ← fpscr */ orr r4, r4, r5 /* r4 ← r4 | r5 */ fmxr fpscr, r4 /* fpscr ← r4 */ /* We will use r4 as k r5 as i */ mov r4, #0 /* r4 ← 0 */ .L3_loop_k: /* loop header of k */ cmp r4, #4 /* if r4 == 4 goto end of the loop k */ beq .L3_end_loop_k mov r5, #0 /* r5 ← 0 */ .L3_loop_i: /* loop header of i */ cmp r5, #4 /* if r5 == 4 goto end of the loop i */ beq .L3_end_loop_i /* Compute the address of C[i][0] */ /* Address of C[i][0] is C + 4*(4 * i) */ add r7, r2, r5, LSL #4 /* r7 ← r2 + (r5 << 4). This is r7 ← c + 4*4*i */ vldmia r7, {s8-s11} /* Load {s8,s9,s10,s11} ← {c[i][0], c[i][1], c[i][2], c[i][3]} */ /* Compute the address of A[i][k] */ /* Address of A[i][k] is A + 4*(4*i + k) */ add r8, r4, r5, LSL #2 /* r8 ← r4 + r5 << 2. This is r8 ← k + 4*i */ add r8, r0, r8, LSL #2 /* r8 ← r0 + r8 << 2. This is r8 ← a + 4*(k + 4*i) */ vldr s0, [r8] /* Load s0 ← a[i][k] */ /* Compute the address of B[k][0] */ /* Address of B[k][0] is B + 4*(4*k) */ add r8, r1, r4, LSL #4 /* r8 ← r1 + r4 << 4. This is r8 ← b + 4*(4*k) */ vldmia r8, {s16-s19} /* Load {s16,s17,s18,s19} ← {b[k][0], b[k][1], b[k][2], b[k][3]} */ vmul.f32 s24, s16, s0 /* {s24,s25,s26,s27} ← {s16,s17,s18,s19} * {s0,s0,s0,s0} */ vadd.f32 s8, s8, s24 /* {s8,s9,s10,s11} ← {s8,s9,s10,s11} + {s24,s25,s26,s7} */ vstmia r7, {s8-s11} /* Store {c[i][0], c[i][1], c[i][2], c[i][3]} ← {s8,s9,s10,s11} */ add r5, r5, #1 /* r5 ← r5 + 1. This is i = i + 1 */ b .L3_loop_i /* next iteration of loop i */ .L3_end_loop_i: /* Here ends loop i */ add r4, r4, #1 /* r4 ← r4 + 1. This is k = k + 1 */ b .L3_loop_k /* next iteration of loop k */ .L3_end_loop_k: /* Here ends loop k */ /* Set the LEN field of FPSCR back to 1 (value 0) */ mov r5, #0b011 /* r5 ← 3 */ mvn r5, r5, LSL #16 /* r5 ← ~(r5 << 16) */ fmrx r4, fpscr /* r4 ← fpscr */ and r4, r4, r5 /* r4 ← r4 & r5 */ fmxr fpscr, r4 /* fpscr ← r4 */ vpop {s24-s27} /* Restore preserved floating registers */ vpop {s16-s19} pop {r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, lr} /* Restore integer registers */ bx lr /* Leave function */ |

As adding after a multiplication is a relatively usual sequence, we can replace the sequence

55 56 | vmul.f32 s24, s16, s0 /* {s24,s25,s26,s27} ← {s16,s17,s18,s19} * {s0,s0,s0,s0} */ vadd.f32 s8, s8, s24 /* {s8,s9,s10,s11} ← {s8,s9,s10,s11} + {s24,s25,s26,s7} */ |

with a single instruction vmla (multiply and add).

55 | vmla.f32 s8, s16, s0 /* {s8,s9,s10,s11} ← {s8,s9,s10,s11} + ({s16,s17,s18,s19} * {s0,s0,s0,s0}) */ |

Now we can also unroll the loop i, again with an unrolling factor of 2. This would give us the best version.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 | best_vectorial_matmul_4x4: /* r0 address of A r1 address of B r2 address of C */ push {r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, lr} /* Keep integer registers */ vpush {s16-s19} /* Floating point registers starting from s16 must be preserved */ /* First zero 16 single floating point */ /* In IEEE 754, all bits cleared means 0 */ mov r4, r2 mov r5, #16 mov r6, #0 b .L4_loop_init_test .L4_loop_init : str r6, [r4], +#4 /* *r4 ← r6 then r4 ← r4 + 4 */ .L4_loop_init_test: subs r5, r5, #1 bge .L4_loop_init /* Set the LEN field of FPSCR to be 4 (value 3) */ mov r5, #0b011 /* r5 ← 3 */ mov r5, r5, LSL #16 /* r5 ← r5 << 16 */ fmrx r4, fpscr /* r4 ← fpscr */ orr r4, r4, r5 /* r4 ← r4 | r5 */ fmxr fpscr, r4 /* fpscr ← r4 */ /* We will use r4 as k r5 as i */ mov r4, #0 /* r4 ← 0 */ .L4_loop_k: /* loop header of k */ cmp r4, #4 /* if r4 == 4 goto end of the loop k */ beq .L4_end_loop_k mov r5, #0 /* r5 ← 0 */ .L4_loop_i: /* loop header of i */ cmp r5, #4 /* if r5 == 4 goto end of the loop i */ beq .L4_end_loop_i /* Compute the address of C[i][0] */ /* Address of C[i][0] is C + 4*(4 * i) */ add r7, r2, r5, LSL #4 /* r7 ← r2 + (r5 << 4). This is r7 ← c + 4*4*i */ vldmia r7, {s8-s15} /* Load {s8,s9,s10,s11,s12,s13,s14,s15} ← {c[i][0], c[i][1], c[i][2], c[i][3] c[i+1][0], c[i+1][1], c[i+1][2], c[i+1][3]} */ /* Compute the address of A[i][k] */ /* Address of A[i][k] is A + 4*(4*i + k) */ add r8, r4, r5, LSL #2 /* r8 ← r4 + r5 << 2. This is r8 ← k + 4*i */ add r8, r0, r8, LSL #2 /* r8 ← r0 + r8 << 2. This is r8 ← a + 4*(k + 4*i) */ vldr s0, [r8] /* Load s0 ← a[i][k] */ vldr s1, [r8, #16] /* Load s1 ← a[i+1][k] */ /* Compute the address of B[k][0] */ /* Address of B[k][0] is B + 4*(4*k) */ add r8, r1, r4, LSL #4 /* r8 ← r1 + r4 << 4. This is r8 ← b + 4*(4*k) */ vldmia r8, {s16-s19} /* Load {s16,s17,s18,s19} ← {b[k][0], b[k][1], b[k][2], b[k][3]} */ vmla.f32 s8, s16, s0 /* {s8,s9,s10,s11} ← {s8,s9,s10,s11} + ({s16,s17,s18,s19} * {s0,s0,s0,s0}) */ vmla.f32 s12, s16, s1 /* {s12,s13,s14,s15} ← {s12,s13,s14,s15} + ({s16,s17,s18,s19} * {s1,s1,s1,s1}) */ vstmia r7, {s8-s15} /* Store {c[i][0], c[i][1], c[i][2], c[i][3], c[i+1][0], c[i+1][1], c[i+1][2]}, c[i+1][3] } ← {s8,s9,s10,s11,s12,s13,s14,s15} */ add r5, r5, #2 /* r5 ← r5 + 2. This is i = i + 2 */ b .L4_loop_i /* next iteration of loop i */ .L4_end_loop_i: /* Here ends loop i */ add r4, r4, #1 /* r4 ← r4 + 1. This is k = k + 1 */ b .L4_loop_k /* next iteration of loop k */ .L4_end_loop_k: /* Here ends loop k */ /* Set the LEN field of FPSCR back to 1 (value 0) */ mov r5, #0b011 /* r5 ← 3 */ mvn r5, r5, LSL #16 /* r5 ← ~(r5 << 16) */ fmrx r4, fpscr /* r4 ← fpscr */ and r4, r4, r5 /* r4 ← r4 & r5 */ fmxr fpscr, r4 /* fpscr ← r4 */ vpop {s16-s19} /* Restore preserved floating registers */ pop {r4, r5, r6, r7, r8, lr} /* Restore integer registers */ bx lr /* Leave function */ |

Comparing versions

Out of curiosity I tested the versions, to see which one was faster.

The benchmark consists on repeatedly calling the multiplication matrix function 221 times (actually 221-1 because of a typo, see the code) in order to magnify differences. While the input should be randomized as well for a better benchmark, the benchmark more or less models contexts where a matrix multiplication is performed many times (for instance in graphics).

This is the skeleton of the benchmark.

main: push {r4, lr} ldr r0, addr_mat_A /* r0 ← a */ ldr r1, addr_mat_B /* r1 ← b */ ldr r2, addr_mat_C /* r2 ← c */ mov r4, #1 mov r4, r4, LSL #21 .Lmain_loop_test: bl <<tested-matmul-routine>> /* Change here with the matmul you want to test */ subs r4, r4, #1 bne .Lmain_loop_test /* I should have written 'bge' here, but I cannot change it without having to run the benchmarks again :) */ mov r0, #0 pop {r4, lr} bx lr |

Here are the results. The one we named the best turned to actually deserve that name.

| Version | Time (seconds) |

|---|---|

| naive_matmul_4x4 | 6.41 |

| naive_vectorial_matmul_4x4 | 3.51 |

| naive_vectorial_matmul_2_4x4 | 2.87 |

| better_vectorial_matmul_4x4 | 2.59 |

| best_vectorial_matmul_4x4 | 1.51 |

That’s all for today.

ARM assembler in Raspberry Pi – Chapter 13 Check_MK, software updates and mount options alarms

Why did you use OR in the first place?

And why did you use the value “#0b011”?

(I won’t make any assumption about your «bit-twiddling» skills so you may skip the following stuff if is too basic for you)

The bitwise OR operation has the following table of truth

0 OR 0 = 0

0 OR 1 = 1

1 OR 0 = 1

1 OR 1 = 1

So given a 0 or 1, we can make sure it is 1 by just OR-ing it with 1. OR-ing with a 0 makes no efect (it leaves the 0 or 1 as it was)

Conversely, the bitwise AND operation has the following table of truth

0 AND 0 = 0

0 AND 1 = 0

1 AND 0 = 0

1 AND 1 = 1

From this table you can see that by AND-ing with a 0 you will always get a zero. AND-ing with 1 has no effect.

From chapter 13 we know that the 32-bit register

fpscrregister allows us to modify the behaviour of the floating point operations. Unfortunately we cannot modify this register directly, so we have to load its value into a normal register, update that normal register and write back that register intofpscr.Bits 18, 17 and 16 of

fpscrare used to set the LEN of the vectorial operations. The LEN value these three bits represent is just the 3-bit number plus 1. This is, when the three bits (18, 17, and 16, respectively) are zero, this is 000, then LEN=1 (it would not make sense to represent LEN=0, so the minimum value that LEN has is always 1).In this chapter we set LEN to 4. So the three bits, 18 to 16, must represent the number 3 (so 3 + 1 will be 4). The number 3 in binary is 011 (bit 18 must be zero, 17 and 16 must be 1). We may assume, thanks to the AAPCS, that

fpscrhas a LEN=1 upon the entry of the function, so as stated above, all three bits will be zero, i.e. 000.Now comes the tricky part, we want to modify just 3 bits of fpscr but we want to leave the remaining ones alone. We only have to set two bits (17 and 16) to be 1 without modifying any other bit. As said above, we have first to load

fpscrinto some register,r4in the example. Now we take the value 3 (I used#0b011in the example, but I could have used #3) and put it into some other register,r5in the example. We want the second of the two 1’s of that 3 to be the bit number 16 (and then, automatically the first of the two 1’s will be the number 17). So we shift left 16 bits using amov r5, r5, LSL #16. Now we have an OR-mask with bits 0000 0000 0000 0011 0000 0000 0000 0000. As you can see, this OR-mask is all 0 except bits 17 and 16 which are 1 (if you count them recall that the rightmost bit is the zeroth). Now we perform an OR between the original value offpscr, inr4, and the OR-mask, inr5. Only bits 17 and 16 inr4will be updated to be 1, all the other will be left untouched (because, recall, OR-ing with a 0 makes no effect). Now thatr4has the value we want, we use it to set thefpscr.We use a similar strategy to set LEN back to 0. In this case, though, we compute an AND-mask. This is, all bits will be 1 except bits 17 and 16 that will be 0. These two bits will clear the bits in the

fpscrbut leave the remaining untouched. Note that it is easier to compute an OR-mask first and then negate all the bits by using themvninstruction. This instruction works exactly likemovbut it applies a NOT to the second operand. In this case the mask will be 1111 1111 1111 1100 1111 1111 1111 1111.I hope this detailed explanation makes clear why we use

orandandto modify LEN.Kind regards.

Thanks again, these tutorials have been a huge help!

</ul> </li> </ul> </li>

I did find a loop control error in three places in the matrix multiply examples, generally around the loop that initializes c[i][j]=0. Though you init the counter to 16, you jump into the loop and decrement by 1 and test, so the loop is running 15…1 — only 15 iterations. The branches should be bge rather than bne in the sequence of instructions following .Lloop_init_test, .L3_loop_init_test, and .L4_loop_init_test.

oops! I did not realize the mistake earlier because the C matrix is already initialized to zero. I fixed the post, thank you very much.

Kind regards,

</ul> </li>

But now I’m running into difficulties and I’m hoping for some insight.

I try to compile the matrix multiplications on my cubietruck/raspberry Pi 2, both having the newer (armv7) Cortex-A7 processor with the vpfv4 coprocessor.

The OS is build with hard-float support and I tried to choose all kinds of fpu settings for compiling, but I always end up with the same result:

your benchmark with the naive implementation takes ~3seconds and all the improved versions have a far worse performance with up to 1m12s.

Is there anything I overlooked? Is the handling of the vector registers differently (and not backwards compatible to your code) on the newer processors?</p>

Thanks for your great work!

well, I do not have a Raspi 2 (I’ll try to borrow one from a friend of mine) and try there.

Your results are a bit surprising but maybe performance in this part is not portable between these two processors. That said, this would be highly undesirable. Make sure you are using the same code as I used to benchmark. I posted it in my github page.

https://github.com/rofirrim/raspberry-pi-assembler/tree/master/chapter14

The file you are interested is

benchmark.s.Kind regards,

real 1m13.286s

user 0m1.748s

sys 1m11.319s</p>

While the naive implementation is like expected:

real 0m4.137s

user 0m3.662s

sys 0m0.020s

It looks like that the program is not really using the coprocessor, but the software implementation of that feature.

It is possible that I overlooked some basics that are necessary in order to use the coprocessor. I was looking for some differences in the usage of newer vfp versions, compared to vfpv2, but I have the impression that it is backwards compatible.

The output of gcc -v ( http://dpaste.com/0G2G8JH#wrap ) suggest that the OS is capable of utilizing the coprocessor.

Thank you for your quick reply.

yes, it looks like your software stack (or at least the compiler) supports “hardware floating” support (usually dubbed as “armhf” or “gnueabihf”). Maybe the operating system doesn’t support it?

Still surprising, though. Looking forward to test it with a Raspi 2.

Kind regards,

This is my neon implementation of your 4×4 matrix multiplication. The main difference is that the neon coprocessor has these 128bit registers which offer some SIMD operations for the parallel processing.

The load and store operations might be a bit messy in my implementation, but since we have only a 4×4 matrix we can easily compute the product of whole rows and columns and unroll another loop.

time ./benchmarkgives me ~0.6s, compared to ~3.5s for the naive implementation.</p>thank you for your implementation using NEON. No doubt it is useful and illustrative, in particular the pairwise additions usage is neat.

Regarding the sequence of loads to load a column, I was wondering if

vld4.f32would be useable here. It will require fourqXregisters (maybe you already run out of them?) but if I understand correctly this instruction, it will already have “transposed” the columns in the registers.Kind regards,

Concerning the load of the A-rows: If I do vld2.f32 {q0, q1}, [r4]!, the order is somehow different and I don’t see exactly why. (maybe the interleaving)</p>

you’re right. Is not useful in this case.

I could not help writing my own version using NEON. You can find it here.

https://gist.github.com/rofirrim/46147612cd00abc4d033

First I tried doing 4 loads of the vector rows of B and then, using vector operations, transposing them as vector columns. But it happens to be faster to just do 16 scalar loads. Then it is simply a matter of doing dot products (i.e, element-wise multiplication and then the sum). I use a full vector row store, but may be 4 scalar stores is faster.

It is slightly faster than you version, but not much more: ~0.50 in the benchmark.

Kind regards,

P.S.: Note that the function should keep all the floating registers it is using. I didn’t bother to change the vpop/vpush but they should be updated.

</ul> </li>

a friend of mine let me use his Raspberry Pi 2 and I was able to reproduce your results.

What happens is that ARMv7 deprecates VFP, so the processor of the Raspi 2 (Cortex A7) does not implement these instructions. Instead, the the Linux kernel implements them in software. Results are correct but they are terribly slow and defeat any possible performance gain.

According to ARM documentation, in ARMv7 you should use NEON instructions (also called Advanced SIMD).

Hope this clears it up.

Kind regards,

I’ll search for the neon/advanced simd instructions and try to implement this.</p>

Keep up the good work!

</ul> </li> </ul> </li> </ul> </li> </ul> </li>

As one who writes code to perform beginning-to-end DSP tasks, this is a serious concern of mine.

Let me hasten to add that whatever negative

consequences of using current tools (e.g., the OS) exist, this in no way minimizes the outstanding work you’re doing in clearly explaining this assembly language.

Warmest regards…

</p>

</form> </div> </div> </div>