Objects and libraries

ARM assembler in Raspberry Pi – Chapter 27

We saw in the previous chapter what is the process required to build a program from different compilation units. This process happened before we obtained the final program. The question is, can this process happen when the program runs? This is, is it possible to dynamically link a program?

Objects and libraries

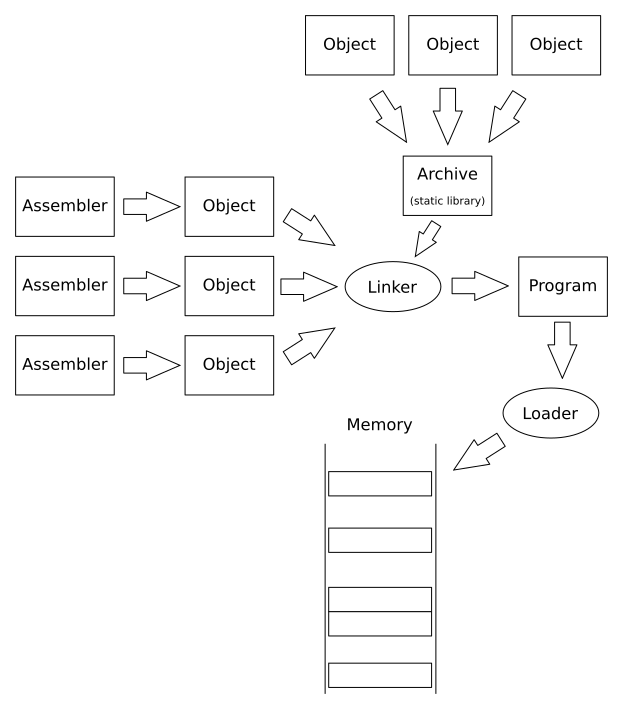

In chapter 26 we saw the linking process, which basically combines several objects to form the final binary. If all the objects we used belonged to our program that would do. But usually programs are built on reusable pieces that are used by many programs. These reusable components are usually gathered together in what is called a library.

In the UNIX tradition such libraries have been materialized in what is called an archive. An archive is at its essence a collection of object files together. When linking a program we specify the archive instead of the object. The linker knows how to handle these archives and is able to determine which objects of it are used by the program. Then it behaves as if only the required objects had been specified.

The C library is an example of this. In previous examples we have called printf, puts or random. These functions are defined in the C library. By using the gcc driver, internally it calls the linker and it passes the C runtime library, commonly known as the libc. In Linux the most usual C library is the GNU C Library. Other C libraries exist that have more specific purposes: newlib, uClibc, musl, etc.

Archives are commonly known as static libraries because they are just a convenient way to specify many objects at the same time. But beyond that, they do not change the fact that the final program is fully determined at link time. The linker still has all the required pieces to build the final program.

Dynamic linking

What if instead of building the whole program at link time, we just assembled the minimal pieces of it so we could complete it when running the program? What if instead of static libraries we used dynamic libraries. So the program would dynamically link to them when executing.

At first this looks a bit outlandish but has a few advantages. By delaying the link process we earn a few advantages. For instance a program that uses printf would not require to have the printf in the program file. It could use an existing dynamic C library of the system, which will also have its copy of printf. Also, if an error is found in the printf of that dynamic library, just replacing the dynamic library would be enough and our program would automatically benefit from a fixed printf. If we had statically linked printf, we would be forced to relink it again to get the correct printf.

Of course very few things are free in the nature, and dynamic linking and dynamic libraries require more effort. We need to talk about loading.

Loading a program

Before we can execute a program we need to put it in memory. This process is called loading. Usually the operating system is responsible for loading programs.

If you recall the previous chapter we had an example where we defined two variables, another_var and result_var, and a function inc_result. We also saw that after the linking happens, the addresses where hardcoded in the final program file. A loader task in this case is pretty straightforward, just copy the relevant bits of our program file into memory. Addresses have ben fixed up by the linker already, so as long as we copy (i.e. load) the program in the right memory address, we’re done.

Modern operating systems, like Linux, provide to processes (i.e. a running programs) what is called virtual memory thanks to specific hardware support for this. Virtual memory gives the illusion that a process can use the memory space as it wants. This mechanism also provides isolation: a process cannot write the memory of another process. Running several programs that want to be loaded at the same address is not a problem because they simply load at the same virtual address. The operating system maps these virtual addresses to different physical addresses.

In systems without virtual memory all addresses are physical. This makes impossible to load run more than one process if any of them overlaps in memory with another one.

To use dynamic libraries, given that the linking process happens in run time, we need a second program, called the dynamic linker. This is in contrast to the program linker or static linker. This dynamic linker will also act as a dynamic loader because it will be responsible to load the required dynamic libraries in memory.

We call this tool a dynamic linker because once it has loaded the code and data of the dynamic library in memory it will have to resolve some relocations. The amount of relocations it has to perform depends on whether the code is position independent or not.

Position independent code

Code can be position dependent or position independent.

Position dependent code assumes that it can use absolute addresses directly. This means that, if we can load the program at the address it expects, nothing else has to be done, which is great. The downside is, of course, if we cannot. In this case we need to fix all the absolute addresses to the new addresses. This means, we load the program in some address (not the one it expects) and then we fix up all the absolute addresses to the new locations. To make this process sensibly efficient relocations will have to be used here. These relocations occur in the code of the program. This means that every process has a slightly different version of the original code in memory. In practice this essentially the same idea as static linking but just delaying at which step the linking happens.

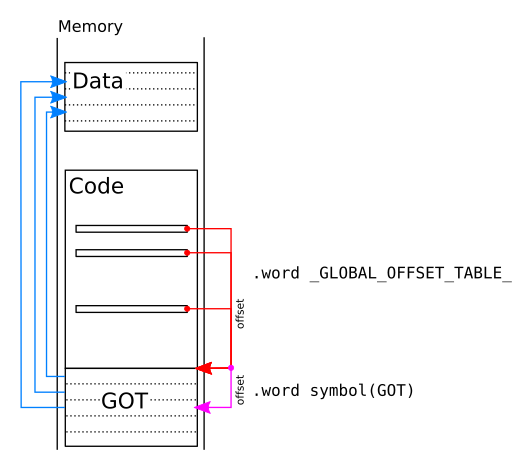

Position independent code (known as PIC) does not use absolute addresses. Instead some mechanism is used on which the program builds relative addresses. At run time these relative addresses can be converted, by means of some extra computation, into absolute addresses. The mechanism used in ELF uses a table called the Global Offset Table. This table contains entries, one entry per global entity we want to access. Each entry, at run time, will hold the absolute address of the object. Every program and dynamic library has its own GOT, not shared with anyone else. This GOT is located in memory in a way that is possible to access it without using an absolute address. To do this, a pc-relative address must be used. So the GOT is then located at some fixed position whose distance to it, from the instruction that refers it, can be computed at static link time.

An advantage of this technique is that there are no relocations to be done in the code at loading time. Only the GOT must be correctly relocated when dynamically loading the code. This may reduce enormously the loading time. Given that the code in memory does not have to be fixed up, all processes using the same libraries can share them. This is done in operating systems that support virtual memory: the code parts of dynamic libraries are shared between processes. This means that, while the code will still take space in the virtual memory address space of the process it will not use extra physical memory of the system. The downside is that because of the GOT, accessing to global addresses (global variables and functions) is much more complex.

Accessing a global variable

As an example of how much more complex is accessing a global variable, let’s start with a simple example. For this example we will assume our program just increments a global variable. The global variable is provided by a library. (I know this is a horrible scenario but this is just for the sake of this exposition)

Static library

Our static library will be very simple. We will have a mylib.s file which will only contain myvar.

/* mylib.s */ .data .balign 4 .globl myvar myvar : .word 42 /* 42 as initial value */ .size myvar, .-myvar |

The .size directive will be required for the case of the dynamic library. It states the size of a symbol, in this case myvar. We could have hard coded the value (4) but here we are making the assembler compute it for us. The expression subtracts the current address (denoted by a dot, .) with the address of myvar. Due to the .word directive inbetween, these two addresses are 4 bytes apart.

Our program will be just a main.s file which accesses the variable and increments it. Nothing interesting, just to show that this is not different to what we have been doing.

/* main.s */ .data .globl myvar .text .globl main .balign 4 main: ldr r0, addr_myvar /* r0 ← &myvar */ ldr r1, [r0] /* r1 ← *r0 */ add r1, r1, #1 /* r1 ← r1 + 1 */ str r1, [r0] /* *r0 ← r1 */ mov r0, #0 /* end as usual */ bx lr addr_myvar: .word myvar |

We can build and link the library and the program as usual.

# (static) library as -o mylib.o mylib.s ar cru mylib.a mylib.o # program as -o main.o main.s gcc -o main main.o -L. -l:mylib.a |

ar, the archiver, is the tool that creates a static library, an .a file, from a set of object files (just a single one in this example). Then we link the final main specifying mylib as a library (the colon in the -l flag is required because the library file name does not start with the customary lib prefix).

Nothing special so far, actually.

Dynamic library

In order to generate a dynamic library, we need to tell the linker that we do not want a program but a dynamic library. In ELF dynamic libraries are called shared objects thus their extension .so. For this purpose we will use gcc which provides a handy flag -shared which takes care of all the flags that ld will need to create a dynamic library.

# dynamic library as -o mylib.o mylib.s gcc -shared -o mylib.so mylib.o |

Now we want to access from our program to the variable myvar using a position independent access.

Actually, the position independent code is only required for dynamic libraries. Our main program could still use non-PIC accesses and it would work for variables in libraries, the linker would take care of this case. But nothing prevents us from using PIC code in the main program. A position independent executable (PIE) needs to do all accesses through the GOT.

Recall, we cannot use a mechanism that forces the code to be relocated (i.e. have its addresses fixed up). Only the GOT can be fixed (it is not code, after all). The address of myvar will be in some entry in the GOT. We do not know which one, exactly, this is a concern of the linker. We still need to get the base address of the GOT first, though.

We saw above, that a PIC access is going to be pc-relative. Given that the program and library will be loaded as a single piece in memory, we can ask the static linker to put the exact offset to the GOT for us. We can do this by just doing

... .word _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_ ... |

Unfortunately this will be a relative offset from the current position in the code. Ideally we’d want to write this

add r0, pc, .word _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_ /* r0 ← pc + "offset-to-GOT" */ |

It is not possible to encode an instruction like this in the 32-bit of an ARM instruction. So we will need to use the typical approach.

ldr r0, offset_of_GOT /* r0 ← "offset-to-GOT" */ add r0, pc, r0 /* r0 ← pc + r0 */ ... offset_of_GOT: .word _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_ |

But that “offset-to-got” must be the offset to the GOT at the point where we are actually adding the pc, this is, in the second instruction. This means that we need to ask the linker to adjust it so the offset make sense for the instruction that adds that offset to the pc. We can do this using an additional label.

ldr r0, offset_of_GOT /* r0 ← "offset-to-GOT" */ got_address: add r0, pc, r0 /* r0 ← pc + r0 */ ... offset_of_GOT: .word _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_ - got_address |

A peculiarity of ARM is that reading the pc in an instruction, gives us the value of the pc offset 8 bytes. So we may have to subtract 8 to the r0 above or just make sure the relocation is already doing that for us. The second approach is actually better because avoids an instruction.

ldr r0, offset_of_GOT /* r0 ← "offset-to-GOT" */ got_address: add r0, pc, r0 /* r0 ← pc + r0 */ ... offset_of_GOT: .word _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_ - (got_address + 8) |

And now in r0 we have the absolute address of the GOT. But we want to access myvar. We can ask the static linker to tell use the offset (in bytes) in the GOT for a symbol using the syntax below.

.word myvar(GOT) |

Now we have all the necessary ingredients to access myvar in a position-independent way.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 | /* main.s */ .data .text .globl main .balign 4 main: ldr r0, offset_of_GOT /* r0 ← offset-to-GOT (respect to got_address)*/ got_address: add r0, pc, r0 /* r0 ← pc + r0 this is r0 ← &GOT */ ldr r1, myvar_in_GOT /* r1 ← offset-of-myvar-inside-GOT */ add r0, r0, r1 /* r0 ← r0 + r1 this is r0 ← &GOT + offset-of-myvar-inside-GOT */ ldr r0, [r0] /* r0 ← *r0 this is r0 ← &myvar */ ldr r1, [r0] /* r0 ← *r1 */ add r1, r1, #1 /* r1 ← r1 + 1 */ str r1, [r0] /* *r0 ← r1 */ mov r0, #0 /* end as usual */ bx lr offset_of_GOT: .word _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_ - (got_address + 8) myvar_in_GOT : .word myvar(GOT) |

We can replace the add (line 16) and the ldr (line 19) with a more elaborated memory access.

16 17 18 | ldr r0, [r0, r1] /* r0 ← *(r0 + r1) this is r0 ← *(&GOT + offset-of-my-var-inside-GOT) */ |

Now we can build the program.

# program as -o main.o main.s gcc -o main main.o -L. -l:mylib.so -Wl,-rpath,$(pwd) |

The -Wl,-rpath,$(pwd) option tells the dynamic linker to use the current directory, $(pwd), to find the library. This is because if we don’t do this we will not be able to run the program as the dynamic loader will not be able to find it.

Calling a function

Calling a function from a dynamic library is slightly more involved than just accessing it in the GOT. Because of a feature of ELF called lazy binding, functions may be loaded in a lazy fashion. The reason is that a library may provide many functions but only a few may be required at runtime. When using static linking this is rarely a problem because the linker will use only those object files that define the symbols potentially used by the program. But we cannot do this for a dynamic library because it must be handled as a whole.

Thus, under lazy loading, the first time that we call a function it has to be loaded. Further calls will use the previously loaded function. This is efficient but requires a bit more of machinery. In ELF this is achieved by using an extra table called the Procedure Linkage Table (PLT). There is an entry for each, potentially, used function by the program. These entries are also replicated in the GOT. In contrast to the GOT, the PLT is code and we do not want to modify it. Entries in the PLT are small sequences of instructions that just branch to the entry in the GOT. The GOT entries for functions are initialized by the dynamic linker with the address to an internal function of the dynamic linker which retrieves the address of the function, updates the GOT with that address and branches to it. Because the dynamic linker updated the GOT table, the next call through the PLT (that recall simply branches to the GOT) will directly go to the function.

One may wonder why not directly calling the address in the GOT or why using a PLT. The reason is that the dynamic linker must know which function we want to load the first time, if we directly call the address in the GOT we need to devise a mechanism to be able to tell which function must be loaded. A way could be initalizing the GOT entries for functions to a table that prepares everything so the the dynamic loader knows the exact function that needs to be loaded. But this is in practice equivalent to the PLT!

All at this point looks overly complicated but the good news are that it is the linker who creates these PLT entries and they can be used as regular function calls. No need to get the address of the GOT entry and all that we had to do for a variable (we still have to do this if we will be using the address of the function!). We could always do that but this would bloat the code as every function call would require a complex indexing in the GOT table. This mechanism works both for PIC and non-PIC, and it is the reason we have been able to call C library functions like printf without having to worry whether it came from a dynamic library (and they do unless we use -static to generate a fully static executable) or not. That said, we can explicitly use the suffix @PLT to state that we want to call a function through the PLT. This is mandatory for calls done inside a library.

Complete example

Let’s extend now our library with a function that prints the value of myvar. Given that it is code in the library it must be PIC code: accesses to variables through the GOT and calls to functions via PLT. Our function is called myfun. It is pretty similar to what we did in the main, except for the increment.

/* mylib.s */ .data .balign 4 .globl myvar myvar : .word 42 /* global variable "myvar" */ .size myvar, .-myvar message: .asciz "Value of 'myvar' is %d\n" .text .balign 4 .globl myfun myfun: push {r4, lr} /* we are going to do a call so keep lr, and also r4 for a 8-byte aligned stack */ ldr r0, offset_of_GOT /* r0 ← offset-to-GOT (respect to got_address)*/ got_address: add r0, pc, r0 /* r0 ← pc + r0 this is r0 ← &GOT */ ldr r1, myvar_in_GOT /* r1 ← offset-of-myvar-inside-GOT */ ldr r0, [r0, r1] /* r0 ← *(r0 + r1) this is r0 ← *(&GOT + offset-of-myvar-inside-GOT) */ ldr r1, [r0] /* r0 ← *r1 */ ldr r0, addr_of_message /* r0 ← &message */ /* r1 already contains the value we want */ bl printf@PLT /* call to printf via the PLT */ pop {r4, lr} /* restore registers */ bx lr offset_of_GOT: .word _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_ - (got_address + 8) myvar_in_GOT : .word myvar(GOT) addr_of_message: .word message |

Now let’s change the main program so it first calls myfun, increments myvar and calls myfun again.

/* main.s */ .data .text .globl main .balign 4 main: push {r4, lr} /* we are going to do a call so keep lr, and also r4 for a 8-byte aligned stack */ bl myfun@PLT /* call function in library */ ldr r0, offset_of_GOT /* r0 ← offset-to-GOT (respect to got_address)*/ got_address: add r0, pc, r0 /* r0 ← pc + r0 this is r0 ← &GOT */ ldr r1, myvar_in_GOT /* r1 ← offset-of-myvar-inside-GOT */ ldr r0, [r0, r1] /* r0 ← *(r0 + r1) this is r0 ← *(&GOT + offset-of-myvar-inside-GOT) */ ldr r1, [r0] /* r0 ← *r1 */ add r1, r1, #1 /* r1 ← r1 + 1 */ str r1, [r0] /* *r0 ← r1 */ bl myfun@PLT /* call function in library a second time */ pop {r4, lr} /* restore registers */ mov r0, #0 /* end as usual */ bx lr offset_of_GOT: .word _GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_ - (got_address + 8) myvar_in_GOT : .word myvar(GOT) |

Let’s build it.

# Dynamic library as -o mylib.o mylib.s gcc -shared -o mylib.so mylib.o # Program as -o main.o main.s gcc -o main main.o -L. -l:mylib.so -Wl,-rpath,$(pwd) |

We can check it is using our library.

$ ldd main /usr/lib/arm-linux-gnueabihf/libcofi_rpi.so (0xb6f3b000) mylib.so => $(pwd)/mylib.so (0xb6f32000) libc.so.6 => /lib/arm-linux-gnueabihf/libc.so.6 (0xb6df0000) /lib/ld-linux-armhf.so.3 (0x7f5cb000) |

And run it.

$ ./main Value of 'myvar' is 42 Value of 'myvar' is 43 |

Yay!

That’s all for today.

Whose is this optimization? A small Telegram Bot in Go